Toward a Living Systems View of Learning & Development

We are arguably in the early days of a shift in Learning and Development which is deeper than a shift in best practices or even in strategy. It could be framed as a philosophical shift: epistemological, ontological, and axiological. In other words, it’s a shift in our ways of learning, of being, and of making decisions.

A good way to consider these foundational shifts is through the lens of a paradigm framework. The work of Clare Graves with Spiral Dynamics offers one such framework, which later influenced many other works including Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations (which a source of inspiration for me transitioning from higher ed to the business world a number of years ago). Inspired by this work and that of several others such as Carol Sanford, we’ll explore just a few paradigms which are most relevant for modern organizational life.

However, before we do, I’ll note that few if any individuals or organizations exists solely in one paradigm. Rather, we likely hold a mix of views and beliefs which determine our decisions and behavior on a daily basis. With increased awareness of these views and where they come from, we can more effectively develop them in the ways our rapidly changing work contexts demand.

The Machine Paradigm

This view emerged with the Industrial Revolution, specifically with the influential work of Frederic Winslow Taylor’s Scientific Management (or ‘Taylorism’). It was later further developed with the work of the behaviorists such as John Watson, B.F. Skinner, and others. In a nutshell, from this paradigm we see people–and the organizations they work in–essentially as machines (or mindless animals) to be controlled and optimized for efficiency. The guiding belief is that people are ultimately controlled by their external environment and that the primary role of management is to build an environment that will produce target behaviors and optimize performance.

Learning from this view, on one hand, is something like installing or updating software on a computer. It is focused largely on knowledge transfer via best practices which represents a specific behavioral code. On another hand, learning from this level can be seen as the conditioned response to external incentives in the environment. These two forms of learning are lumped together here because they both ultimately rely on external direction from sources of expert authority that possess clear answers.

One issue (of many) with working from this paradigm is that it depends on someone having clarity about exactly what needs to happen, how it needs to happen, when, by whom, etc. While it is relatively well-suited to simple and predictable environments, it becomes ineffective in more complex environments where greater levels of agility are needed in the face of uncertainty and rapid change.

The Humanistic Paradigm

This view came to prominence in the 1950’s with the emergence of humanistic psychology and thinkers like Abraham Maslow, who’s Hierarchy of Needs framed a path toward the highest-stated aim of self-realization. It was later influenced by the civil rights movement and social values such as diversity, equality, and inclusion. This view arose in direct opposition to the dominant behaviorist view that, to quote John Watson, “there is no difference between man and brute.” On the contrary, it holds the belief that human beings possess unique needs which must be considered for them to fully realize their potential.

Learning from this view is human-centered and focuses on the realization of human potential. It can also be associated with a constructivist view of knowledge which emerged around the same time, or the view that knowledge is constructed by the individual based on their own previous experiences. This paradigm is also often associated with postmodernism, which rejects claims of universal truth and emphasizes the idea that knowledge is ultimately subjective and relativistic.

One issue with working from this paradigm is that it can lead to a very inward-facing way of being. An over-emphasis on equality and relativism can lead to a lack of discernment and strategic thinking. For example, group-think often emerges within echo chambers which lack consideration of external perspectives and reinforce confirmation bias. In some cases, unfortunately not so rarely, there is outright contempt for any contradicting ideas and a tendency to shut out opposing views. False senses of certainty arise within rival factions which can lead to conflict, sometimes of a violent and destructive nature. In such systems a fear of offending or challenging group ideals presents a significant barrier to learning and development.

The Living Systems Paradigm

In the 1960’s Proctor and Gamble implemented a breakthrough approach to developing their people and their businesses at the same time, led by Charles Krone. Notably, this approach was kept secret for many years and is still unknown to most. Around the same time, there was a lot of breakthrough work happening in biology, cybernetics, and other fields which informed a new way of thinking called Systems Thinking. Since then, there have been an increasing number of scholars and practitioners exploring how this view may be applied to the development of organizations and the people in them. In the 1990’s Peter Senge highlighted Systems Thinking as the key discipline for building a learning organization in his well-known book The Fifth Discipline.

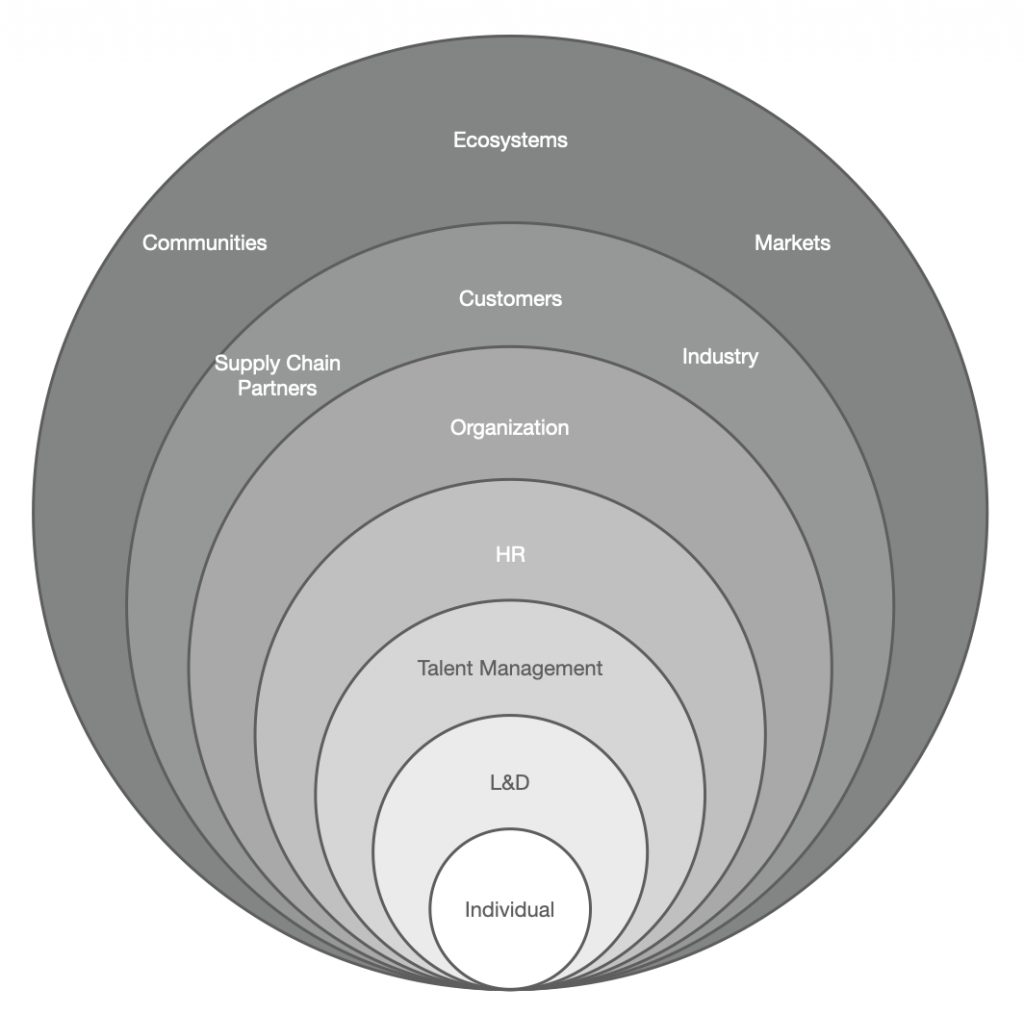

There is, however, an important distinction to be made between many popular approaches to systems thinking and working from a Living Systems paradigm. For example, it could be argued that there is a good deal of influence from the Mechanical paradigm in traditional systems thinking approaches. The key difference is that living systems are not mechanical, but rather are evolutionary. They operate on a different set of principles than non-living mechanical systems do. When we work to understand these principles and are guided by them in what we do and how we interact with our stakeholders, we are more aligned with the natural evolutionary forces at work in all living systems. These systems include individuals, families, teams, organizations, communities, markets, ecosystems, and so on.

Principles of Living Systems and how we can apply them in L&D

Our personal mentor Carol Sanford, who worked with Charles Krone and has been helping organizations such as DuPont, Colgate, Google, and many others develop toward a Living Systems way of working for over 40 years, outlines 7 first principles in her book Indirect Work. We’ll briefly explore how each of these may be applied in our work in L&D.

Principle #1: Wholes

Often Learning & Development is approached in a very fragmented way. We isolate a problem and we implement a program to fix it. From a Living Systems view, we think about learning in terms of whole systems. We facilitate the simultaneous development of individuals, teams, the organization, and different stakeholder groups (including the environment), creating rich contexts for the learning experiences we create which connect learners to the bigger picture and facilitate strategic thinking. This principle can help us create a greater impact through our work, while avoiding the unintended consequences of working in a fragmented way and losing our connection with the bigger picture.

Principle #2: Potential

From this paradigm we shift from a primary focus on problem-solving, to one of actualizing potential. Whereas the Humanistic view tends to focus on individual potential, the Living Systems view focuses on both individual and systemic potential. Learners are encouraged to explore and imagine the unrealized potential of their teams, organizations, communities, industries, etc. In doing so, the motivation for learning and development is rooted more firmly in an inspiring and holistic sense of the future rather than simply keeping the machine running and the paycheck coming in. Learners are pulled forward with a greater degree of intrinsic motivation which results in higher engagement, retention, and performance.

Principle #3: Essence

From this view, we see that every individual and every living system is unique. Therefore, we avoid the common practice of categorizing which typically leads to inauthentic and mechanistic behavior. L&D from this perspective is about supporting both individuals and larger systems to express their unique essence in a value-adding process. We can help our stakeholders discover this unique essence and how they aspire to express it through their work, rather than reinforcing superficial identities that present barriers to meaning and intrinsic motivation. At the same time, we can help others learn to see in this way — to view their stakeholders as unique which helps them avoid the misguided belief that they already know and understand them based on superficial categories or labels. This shift generates a much more curious mindset and leads to others learning far more effectively from each other as they form relationship that go deeper than the ‘functional masks’ we have traditionally worn at work. We create cultures where we can show up more authentically and tap into deeper sources of creativity and inspiration.

Principle #4: Development

We are of course very familiar with this term in L&D, but we can also see how its meaning changes depending on what paradigm we are working from. For example, from the Mechanistic view we tend to see learning and development deterministically. In other words, we attempt to identify all of the variables related to a specific problem and try to predict/control the outcome through manipulating those variables. We often have clear behavioral outcomes, for example, which we work backwards from to achieve the goal. The Mechanistic or environmentally deterministic view is contradicted by insights produced by work in evolutionary biology and other fields. These insights show that living systems develop through a process called structural coupling: internal changes are triggered, rather than determined, by environmental impressions. In other words, we can’t control living systems. They are ultimately self-determining. What we can do is help to build the capacity of the system for self-determined, continuous development. We have elsewhere referred to this as developmental capability.

Principle #5: Nestedness

A fundamental barrier to creating experiences that are contextually-rich and connect learners to the bigger picture is that from an old way of thinking, doing so requires piling on a lot more information and things tend to get very complicated. We risk losing our learners by zooming out and dumping this extra load on them. So we stay zoomed in, working in a fragmented and mechanical way that limits meaning and engagement. From a Living Systems view, we learn to see this rich systemic context as a pattern of nested wholes: individuals nested within teams, teams within organizations, organizations within communities and ecosystems, etc. We also learn to think about these systems as each possessing a unique essence. This allows us to see past the superficial information which overloads us to discern patterns on a more fundamental level. We get a feel for these patterns and we become curious to understand them through our work. How does this system aspire to express its unique essence through a value-adding process within the larger systems it is a part of? This way of seeing allows us to embrace the complexity we face without being threatened by information overload.

Principle #6: Nodes

One very common way to think about expanding our influence as a team or organization is through the lens of scaling. Yet this is arguably a mechanistic way to think about growth. As Sanford writes, “Scalability has to do with imposing an imported idea of what’s right and good, a so-called best practice, rather than starting from the essence and wholeness of distinctive living entities.” So rather than thinking about creating more impact through the broader transfer of best practices, as is common in L&D, our strategies shift toward nodal intervention. For example, we look for the places in the system where we can generate broad ripple effects with relatively low inputs and precise action. A node is such a place, where there is a high degree of connectivity to other elements in the system and there is a lot of energy flowing through. Sanford compares nodes to acupuncture points in the human body. Yet seeing these points requires something deeper than a mechanical approach to analysis: it requires a type of conscious awareness of how energy is moving through the system that is not common in modern business practice.

Principle #7: Fields

We can think about fields as the energetic states of a system. By learning to perceive and shift such states, we can affect much greater change than we can when we are simply ‘tinkering’ on the level of reactively solving problems to keep the machine running. Fields are affected by many factors including the environmental and cultural. As with perceiving the nodal patterns within a field, to perceive and understand the field as a whole requires new ways of seeing and new levels of consciousness. We have to be able to look past the superficial to the patterns underneath our immediate perceptions. David Bohm referred to this as the implicate order. It is from this field that everything within it arises and changes, and it is the field itself which connects these things into a whole. As we develop our ability to see it and discern its patterns, we can become more strategic and effective in our work. We gain a deeper understanding of a system’s essence. We begin to see what it is trying to express and how it aspires to contribute to the larger whole. We learn how we can support it to do so by resolving creative tensions and giving rise to emergent, innovative solutions that we could never have predicted from a mechanical way of thinking.

Taken together, these principles inform a way of thinking and working in L&D that is very different from many common practices. Yet there is some apparent movement in the direction of a Living Systems approach: toward growing decentralized, integrative learning networks with a greater emphasis on developing capabilities and culture. However, most organizations are still stuck in the lower paradigms. There remains much work to do as we navigate this shift together, toward a world where learning is more central to life and where L&D leaders are creating more strategic value than ever.

Founder and CEO at The Continuous Learning Company

Tom helps L&D teams create more strategic value by developing capabilities and cultures of continuous learning.

Latest posts by Tom Palmer (see all)

- Beyond Growth Mindset: Building Coevolutionary Capacity - April 20, 2023

- 7 Principles of Regenerative Learning & Development - March 15, 2023

- L&D Must Go Deeper: Shifting Epistemology - January 16, 2023